During the 1916 Rising in Ireland, there were many people who invested their time to the cause. Amongst these people, there was a woman named Rosanna Hackett was called Rosie Hackett (Rosanna by birth). She… More

Walking Through History – A perspective on the 1916 rising

The 1916 Rising or the Easter Rising was an armed insurrection that took place in Dublin, Galway, Wexford, and Meath but it happened mainly in Dublin. The Rising was an attempt made by Irish Republicans to end British rule in Ireland. It was the most significant uprising since the United Irishmen’s rebellion in 1798.

On the 24 April 1916, Easter Monday, 1,500 Irish Volunteers, together with around 200 members of the Irish Citizens Army seized the General Post Office (G.P.O.) on O’Connell Street and other buildings in Dublin.

From the front of the G.P.O. Patrick Pearse, Commander in Chief of the Irish Volunteers and the president of the Provisional Government of the Irish Republic read out the Proclamation that declared Ireland a republic free from Britain. ‘We hereby proclaim the Irish Republic as a sovereign Independent State’

Initially the British response to the rebel’s actions was uncoordinated as they were caught by surprise and unprepared. In the days to follow, Martial Law was declared giving civil power over to Brigadier- General Lowe who brought in reinforcements from England, Belfast and the Curragh. At the end of the week British military presence had increased from around a thousand soldiers to over 16,000. The British military had access to a light gun boat called the Helga which sailed up the river Liffey and shelled Liberty Hall and the G.P.O.

Surrender didn’t come until Saturday the 29 April. After days of shelling had caused fire to spread to the walls of the G.P.O. and surrounding buildings the rebels were forced to evacuate their headquarters there and retreat to Moore Street. From this new position Pearse through Elizabeth O’Farrell, a nurse, would begin a process of surrender.

Pearse surrendered unconditionally to Brigadier- General Lowe.

In the aftermath of the Rising 64 rebels and 132 Crown forces had been killed. On top of this about 320 civilians had been killed with extensive damage done to the city.

The 1916 Irish Sufferagettes

In 1916 suffragettes had been around since the late eighteenth century even in Ireland. Their hope was to give thirty year old white woman, who own property, the ability to vote in public elections.This law came to pass in 1918 in the United Kingdom and Ireland. This was a just cause that would further the women’s liberation movement in the west with a hope to eventually become more inclusive of all types of women across the globe.. In Ireland, Independence was the main agenda, and suffrage was to become a more pressing issue in the next two years. Ireland’s most well know female commander and soldier in 1916, Countess Markievicz , was a know suffragette and the first woman elected to the British House of Commons. As well as being the only female cabinet minister in Irish History until 1979 and the second female government minister in Europe.

In 1916 Maud Gonne, was in France trying to get Cuman Na Mban some recognition for the organization.They both became synonymous nineteenth century feminism and the Irish suffragette movement after the Rising.

Fashion and gender are deeply interconnected in society, so the suffragettes,who included Emmeline Pankhurst, who was a British political activist and a leader of the British suffrage movement. Who along with her daughter Christine, were know for arson, smashing and picture slashing. They were aware of “ugly” deranged bra burning stereotype that is associated with women’s liberation. They sought to present as feminine through contemporary fashion, as they were very aware of the media glare and public perception,

Louie Bennett and Edith Somerville were apart of the Irish Women’s Suffrage Party and were nationalists at this time. The IRA had women soldiers who also carried guns. There is a contrast between the suffragettes and women of the IRA as well as other more militant armies and how the present themselves as they fight in a revolution as a woman in the early 1900s. Both cases show you must either present as a masculine soldier or a “proper women” to be taken seriously. Highlighting the need for feminism and the power of protesting and using your abilities to makes a difference in a constricting and patriarchal world.

Emmeline Pankhurst: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/pankhurst_emmeline.shtml

Countess Markievicz: http://www.irish-society.org/home/hedgemaster-archives-2/people/countess-constance-markievicz

Women’s Voting rights in Ireland: http://www.dublincity.ie/main-menu-services-recreation-culture-decade-commemorations/first-time-votes-women-elections-1918

Michael Collins – A Movie Review

Michael Collins is a movie based on the life of the Irish rebel and leader who rose to prominence after the 1916 Rising. He is portrayed by the actor Liam Neeson and the film shows Michael’s action in the years following the failed Rising, such as the formation of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and the signing of the treaty that eventually gave Ireland it’s freedom, though not what was originally desired by the Republican party.

The movie starts off with the 1916 Rising at its breaking point, as the rebels are surrendering to the British military and the leaders are taken away to be executed. Throughout the course of the movie we’re treated to a upstanding performance of Eamon Devalara, played by the late Alan Rickman.

After the leaders of the Rising are killed the movie skips forward to when Michael, and the other fighters who were arrested after the Rising, have been freed. Michael immediately goes back to stirring up trouble for the British Government, and using his ability to inspire the common people he uses unconventional weaponry to capture essential supplies for the start of his army.

Throughout the course of the movie we see how the Irish people fought the British Empire in a completely new way to what they were used to, using guerilla warfare they strategically attacked and crippled their military presence and grip on Ireland to the point where they send in a new force, the Black and Tans, who were mostly comprised of criminals. This however worked against the British even more until eventually they call a ceasefire and are willing to negotiate a treaty.

The treaty that is agreed upon however results in Ireland forfeiting the North, this leads to a division between Michael and the Republics loyalists against Eamon De Valera’s anti-treaty supporters. In the ensuing Civil War many Irish people are killed and it comes to a dramatic end when Michael is killed by an ambush in his home county of Cork, where he was hoping to bring things to a peaceful resolution with De Valera.

The movie is an interesting watch because it isn’t a simple firefight or good and evil plot. Both sides are shown performing horrific acts, the Irish rebels are depicted as especially brutal, killing spies and officials who were causing problems for them. Eamon is shown to be highly opposed to these underhanded yet highly efficient strategies, which leads to a major rift between him and Michael, who is willing to fight, not for a blood sacrifice such as the 1916 Rising, but for victory.

The movie is an interesting watch because it isn’t a simple firefight or good and evil plot. Both sides are shown performing horrific acts, the Irish rebels are depicted as especially brutal, killing spies and officials who were causing problems for them. Eamon is shown to be highly opposed to these underhanded yet highly efficient strategies, which leads to a major rift between him and Michael, who is willing to fight, not for a blood sacrifice such as the 1916 Rising, but for victory.

Liam Neeson does an outstanding job portraying the conflict within Michael as he is forced to turn on his fellow Irish men, showing the pain and conflicted feelings perfectly.

Eamon De Valera is wonderfully brought to life by Alan Rickman, his particularly unique voice making De Valera’s speeches seem all the more impactful, displaying him as a charismatic leader.

Julia Roberts adds an interesting twist to the film. Showing off Collin’s more human side, allowing us to see how difficult his choices are.

The cast is made up of many other notable names, all who bring their A-Game to the film, such as Stephen Rea as Ned Broy, Charles Dance as Soames and many more.

The Irish Flags

This year marks one hundred years since the 1916 Easter Rising. To commemorate this historic event almost every building in Dublin is flying the Irish tricolour. The tricolour was created in 1848 for Thomas Francis Meagher. The flag is green and orange with a strip of white between them, Meagher said that…

“The white in the centre signifies a lasting truce between the ‘Orange’ and the ‘Green’ and I trust that beneath its folds the hands of the Irish Protestant and the Irish Catholic may be clasped in heroic brotherhood.”

While the tricolour is perhaps the most popular flag on show in our nations capital, it isn’t the only one.

One of the oldest flags associated with Ireland is the golden harp on a green background.

This flag was a symbol for Ireland back in the 18th century, it was used by the Society of United Irishmen during the rebellions of 1798 and 1804. The flag was used during Daniel O Connell’s repeal of the Union act, during which the Irish fought for the creation of a fully independent Kingdom of Ireland, of which Victoria, Queen of Great Britain would rule over equally. .

The flag fell out of favour around WW I when Irish people associated it more closely with the war propaganda, in which it featured heavily. The final nail in the coffin for the Golden Harp flag came after the 1918 election where Sinn Fein defeated the Irish Paramilitary Party and supplanted the Golden Harp with the Irish tricolour which became the Irish flag. Following their win Sinn Fein had the tricolour written into the Irish constitution as the Irish flag, cementing it as the only flag of Ireland.

‘The national flag is the tricolour of green, white and orange’ – Article 7

Another flag which has significance in this centenary is the ‘Irish Republic’ flag.

The Irish Republic flag was flown over the GPO Easter week and has special significance to the republican movement and the Rising unlike other flags at the time. The Irish Republic flag is the only flag that was made especially for the Easter Rising, all other flags had existed prior to that.

The Irish Republic flag was painted by hand in the home of Countess Markievicz by Theobald Wolfetone Fitzgerald. It is said to have been made out of some green bed sheet that was lying around. It was painted in the colours of the Irish Tricolour.

After the Easter Rising the Irish Republic flag was removed from the GPO by a British Soldier and eventually ended up in the Imperial War museum.

In the year 1966 the flag was gifted back to the Irish to mark half a century since the Rising.

The flag is currently on display in the Proclaiming a Republic- The 1916 Rising, in the Irish National Museum in Collins Barracks.

Where the ladies at? The removal of woman from Irish History and Arts

The centenary celebrations of the 1916 Rising dealt with a number of themes and issues, one of the key themes of the years celebrations was the role that women played in 1916. The women of 1916 have gone without recognition for generations, and finally they are being celebrated for their part in the Rising.

Irish women have been side-lined from Irish political history especially in regards to their part in the fighting during Easter week 1916. A good example of removal of women from political history is the cropping out of Elizabeth O’ Farrell and her feet from the famous photo of Pearse’s surrender.![original[1]](https://sarahbyrnesite.files.wordpress.com/2016/04/original1.jpg?w=760)

Elizabeth O’Farrell was a member of Cumman na mBan who were the women’s branch of the Irish Military Paramilitary. She worked as a nurse in the GPO and joined the fighters when they moved on to Moore Street during Easter week. Once the fighting was over, O’Farrell carried a white flag and the official surrender from Pearse to the British Guard but she was then edited out of the official surrender photo. Being edited out of moments of historical importance, such as o’Farrell was, began a common trend of side-lining and moving women from the polis (political) and returning them to the oikos (home).

Éamon de Valera played a key role in reducing the roles of women outside the home especially when he rose to power as Taoiseach of Ireland in 1937. As a leader in the 1916 rising deValera held the Bolands Mills on Grand Canal Dock with a troop of 100 poorly armed soldiers. When joined by women of Cumann na mBan, deValera absolutely refused to have any women involved in the fighting and demanded that they return home. Many of the female insurgents believed that this is why the Bolands Mills didn’t last as long during siege.

![countess[1]](https://sarahbyrnesite.files.wordpress.com/2016/04/countess1.jpg?w=308&h=552)

Once deValera became a key political power in the 1930’s he was involved in the further side-lining of women by reducing their position within the Irish constitution to that of household caretaker, and writing that into law.

“ Article 41

2. 1 In particular, the State recognises that by her life within the home, woman gives to the State a support without with the common good cannot be achieved.

The State shall, therefore, endeavour to ensure that mothers shall not be obliged by economic necessity to engage in labour to the neglect of their duties in the home.”

Women became more symbolic in Irish culture, this can be seen as having root in the theatrical writings of Irish Literary Revival, a literary attempt to revive Irish writing. A play which came out of this movement, Cathleen Ní Houlihan by Lady Gregory and W.B. Yeats, features the title character Cathleen as a symbolic representation of Ireland. Irish theatre has always given a symbolic role to women, especially when it comes to representations of 1916.

![3fd3cb39ae2cfbcce7bb7bdcf0c4d62a[1]](https://sarahbyrnesite.files.wordpress.com/2016/04/3fd3cb39ae2cfbcce7bb7bdcf0c4d62a1.jpg?w=760)

The symbolic nature of women is epitomised in the lack of statues in the city centre to commemorate women. With 70% of the statues of women being as a representation, rather than to commemorate an actual woman.

Statues that are of actual women include two of the Countess Markievicz, one full body statue on Tara Street and a bust in St. Stephens Green, and a statue of Margret Ball on Cathedral Street. Ball was a devote Catholic who was punished by her son and publicly tortured to deny her faith, which she did not do.![ie027[1]](https://sarahbyrnesite.files.wordpress.com/2016/04/ie0271.jpg?w=760)

Women are represented as being symbolic, such as Anna Livia known locally as ‘The Floozie in the Jacuzzi’ who is supposed to represent the river Goddess for whom the Liffey is named. She is doubly symbolic as she appears in James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake as a character who also embodies the river.

![9626426107_c3818f5593_z[1]](https://sarahbyrnesite.files.wordpress.com/2016/04/9626426107_c3818f5593_z1.jpg?w=432&h=432)

There is also, probably the most famous statue in Dublin, Molly Malone. Known locally as ‘The Tart with the Cart’ on Sulfolk Street. Molly Malone is a romantic idea as to what life in Dublin was like in the 17th Century. The female statues are the only statues in Dublin that are subjected to offensive nicknames and continuous sexual groping so much so that the bronze had worn away on the chest of Molly Malone. The sexualisation of these female statues further diminishes their significance and their position within the cityscape of Dublin.

![mollymalone-oct2014-3[1]](https://sarahbyrnesite.files.wordpress.com/2016/04/mollymalone-oct2014-31.jpg?w=760)

Women are also represented as symbolic in the statues of the Famine People, Children of Lir, Famine Monument, Three Fates, Eire Sculpture and the two women with the bags.

![eire-blog[1]](https://sarahbyrnesite.files.wordpress.com/2016/04/eire-blog1.jpg?w=457&h=331)

It is only in recent years that the first bridge was named after a woman, the Rosie Hackett Bridge. After months of deliberations Rosie Hackett was chosen as the name for the bridge.

![index[1]](https://sarahbyrnesite.files.wordpress.com/2016/04/index1.jpg?w=203&h=246)

![aerialviewrosiehackettbridge[1]](https://sarahbyrnesite.files.wordpress.com/2016/04/aerialviewrosiehackettbridge1.jpg?w=461&h=307)

At the unveiling of the bridge there were, reportedly, no women present. Still in 2015 women are being side-lined from the important moments in Irish history. In the Abbey Theatres preparations for the 2016 centenary, female playwrights were excluded from theatrical line up with only one in ten plays being performed having been written by a woman.

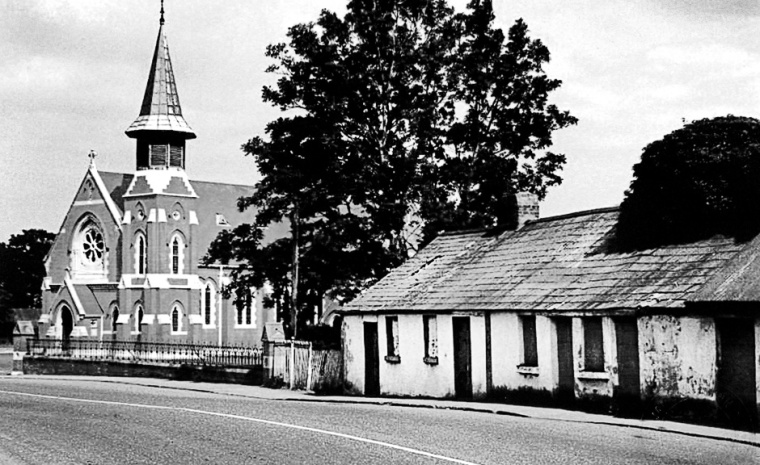

Donabate during the Rising 1916

As 2016 is the year of commemoration for the centenary of the 1916 Easter Rising, which has been marked as the first strive towards Ireland’s freedom, my interest was sparked to look into my own town’s local history in relation to the events of the rising. I was unaware of any contribution from the small village of Donabate, what I discovered was that not only were there men from the village that joined the leaders in the city centre but also a “battle”, if you can call it that, right in the centre of Donabate itself.

On the Wednesday of Easter week 1916 the Irish Volunteers were involved in fierce combat with the British Army, in various outposts across Dublin City, in locations such as, the GPO and Boland’s Mill. At the same time the Fingal Brigade of the Irish Volunteers engaged in some armed activity between Donabate and Swords.

The local armed republicans had been active in Fingal since Easter Monday when they originally assembled at Knocksedan Bridge at the back of River Vally. By the Wednesday the Republicans, led by Kerryman Thomas Ashe, had planned to seize the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) police barracks in both Swords and Donabate, as they were acting under British command.

In Swords the surrender of the police was quick and uneventful. However, things were quite different in Donabate and the attack on the original RIC barracks, which was located behind what is now Keeling’s pub, would be the first instance of the Fingal unit coming under British fire.

The following is an account from Irish Volunteer Charlie Weston (who’s grandson still lives in Donabate);

‘We were ordered to take a pickaxe, sledge and crowbar and burst in the door. Six of us rushed up to the door and shouted at the police to surrender or we would break in the door. The answer was a revolver shot fired out of the top window. Immediately the window was riddled with bullets from our men. We proceeded to break in the door. After a few seconds the door frame gave way and the door went in. There was an inner iron door with a chain on it. When the door went in they immediately shouted they would surrender. They could not get the iron door open, but one of them threw a rifle through the top window as a token of surrender.’

Captain Charles Weston

The RIC Constable Thorpe had been shot in the hand when the RIC police surrendered. After the brief shootout and prompt surrender, the republicans seized all the available arms in the police station. While in the RIC station Thomas Ashe discovered the intelligence files which had notes with information on local republican volunteer’s names and activities.

After this encounter the volunteers returned once again to their billets at Kileek (near Saint Margaret’s) for camp. Until joining with the republican forces to capture Ashbourne, the only town “freed” during the 1916 Rising.

Women’s fashion and societies standards

In our culture, clothing has always been tied to the perception of how others view us and they believe to know who we are and what our position in society is. This narrow minded approach is continuously perpetuated by marketing and the need to label. Around 1916, clothing, as it is now, was heavily tied to gender roles, as it was seen as a scandalous act for a women to wear pants. Today women are seen as being more interested in fashion than politics so often clothes are more expensive for women, for example a white t-shirt for women is more expensive than one made for men, even though there is no major difference, except the target audience and general size.

In 1916, fashion was even more problematic, as it differentiated between the male and female soldiers even further. Female soldiers were at disadvantage as they were expected to wear long skirts in battle, as this was proper way for women to dress. Cumman Na Mban (the Irish Republicans woman’s paramilitary organization, which in 1916 was an auxiliary of the Irish Volunteers) members were not confined to being couriers or procuring rations for the males soldiers but they also fought alongside their male counterparts in the rebel garrison. The uniforms of Cumman Na Mban and the Irish Citizen Army were very similar as both uniforms were of a dark green colour, however the female jackets were much coarser and heavier than their male counterparts. This tweed material had a V-neck, which some of these women accessorised with bandoliers, pocketed bells for holding ammunition and they were usually slung over the shoulder in a sash-style as well as white kit bag. They also wore a belt buckle in a shape of an S, which was very common among armies in the last two hundred years. In the Irish Citizen Army, equality was a principle they strived as they took in women on equal rank to men, though on record there was no more than thirty women in the army who tended to act as nurses and messengers rather than fighters.

Margaret Skinnider was part of the Irish Citizen Army. She was twenty three years old and an excellent marks woman. She was shot during the rising and sought compensation for this. She was sent to prison twice, once during the War of Independence and then again in 1923, when she was became the Paymaster General of the Provisional Irish Republican Army. The reasons for both of these arrests are unclear. She struggled to be seen as a soldier throughout the rest of her life as in the eyes of the law she was entitled to nothing, not even her pension: “were applicable to soldiers as generally understood in the masculine sense”. This was the law’s response when she seeked her military pension. Once again femininity was apparently a weakness even though Margaret Skinnider has proven versatility and strength. She was a skilled women in a male dominated environment where it took decades to recognise her as an equal to men who were often less experienced than her and worked half as hard as she did for the recognition and equality she so richly deserved and yearned for.

Irish Citizen Army:

Irish Insurgents

http://www.irishtimes.com/news/the-forgotten-role-of-women-insurgents-in-the-1916-rising-1.1030426

Margaret Skinnider:

About 1916SAMPLED

1916 SAMPLED is created by 2nd year DBS Arts students. The name 1916SAMPLED is created from the participants initials and reflects the idea that the students chose to to ‘sample’ a variety of aspects surrounding the 1916 Easter Rising in Ireland.

We (SAMPLED) have chosen topics such as: the role of women during the Rising and how they are remembered, the fashion of 1916 and we also took a closer look at both forgotten and remembered heroes of the Rising.

Through the creation of 1916SAMPLED we have learnt, that sometimes, you don’t have to look very far to find that history is closer than you think.

(The image above shows students and teachers of Fatima National School Cloone in 1916 / courtesy of Leitrim Observer)